What do collaborative teams have in common? From a Psychology student

Management

The very nature of organizations consists on collaboration, which means two or more people working together towards shared goals. We know collaboration is a good thing: in doing so, people can achieve bigger goals than the ones they would attain working individually. However, both personal experience and scientific studies tell us that it isn’t as simple as putting a group of people together for the positive effects of collaboration to happen. In fact, working together can also be detrimental.

As manager and Psychology student at UOC, I’m always trying to understand better group dynamics, so that I can influence my teams to achieve more ambitious results. During the last few years, I’ve been observing the context and behaviors that promote their success as teams. Here are some of them:

Specialization. Apart from the operative benefits of role specialization, it consists on letting each person do what they are best at.

Support. Showing care and appreciation for each other during tough personal times is key to building trust. That trust enables people to work together better. The way of demonstrating emotional support and care might differ between cultures, but the impact is likely to be the same.

Culture of team success. If the success of my teammate benefits my team, then it’s my success as well. A team-oriented culture should reward collaboration over competition between individuals, reducing conflicting goals, so it’s on the individual’s interest to help others succeed.

Decision-making process. A defined process enables streamlined, effective and less stressful decision-making. Frameworks like DACI or structured RFC processes foster cultures more accepting of change.

Spaces and interactions intentionally designed to promote respect, connectedness and openness within groups, as shown by recent research.

On the other hand, here are a few aspects that prevent positive collaboration, like:

Unnecessary blocking dependencies. This happens when some team members are blocked by others to achieve their objectives. It hurts productivity and causes frustration.

Knowledge silos. While specialization isn’t bad, knowledge silos imply that a person or small group of people are the only ones with the knowledge to perform certain tasks or make certain decisions. Obviously, this creates blocking dependencies, increases bus factor and enables negative power dynamics around control of information.

Not overcoming the storming stage of team development. In Tuckman’s team development model, storming is the second stage that teams go through. It’s characterized by the conflicts and power struggles caused by team members exploring their limits and where they fit in the team. This stage is very unproductive in terms of results, so it’s the manager’s responsibility help the team get through it.

In the field Social Psychology, scientists have also studied two opposing phenomena that affect collaboration:

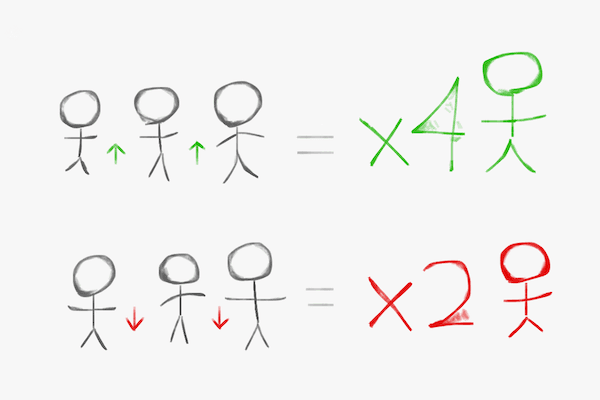

Social facilitation, referred to the finding that individuals sometimes perform better when they are in the presence of others or being observed. Scientists have observed the fascinating fact that being observed helps with simple tasks, but makes individuals less productive with complex tasks.

Social loafing, as the tendency to put less effort on tasks done with a group compared to tasks done individually. Some types are easier to identify, like diffusion of responsibility, while others are harder to spot from the outside, like avoidance of putting more effort than others. It’s on the manager to clear the uncertainty that causes teams to develop these dynamics.

Zlatian Iliev, tech lead at Splash, proposes to extend the idea of positive collaboration to any relationship, as achieving more than the sum of its parts. Think of your friendships, your family and your partner. Are those groups of people better together than separate? Are they enabling their members to be better than if they were alone? While it can’t be measured in terms of output, the idea is still applicable, and it’s a beautiful one in my opinion.